How I Carry Diabetes Supplies For Travel and Long Bike Packing Trips

People will often see Janet and me bikepacking and comment, “Wow, you guys are traveling light!” Usually, they say next, “Well, you must not be bringing a tent.” We reply, “No, we have a tent.” The next refrain is usually, “well, you definitely don’t have a stove.” We assure them, “we have a stove too. In fact, we’re also carrying a drone and a computer.” I usually stop there as they try to figure out how this is possible… but the irony is that I haven’t even mentioned our biggest single carry yet: My Diabetes supplies!

Traveling Light! All the equipment for two people riding 50 days on the Baja Divide.

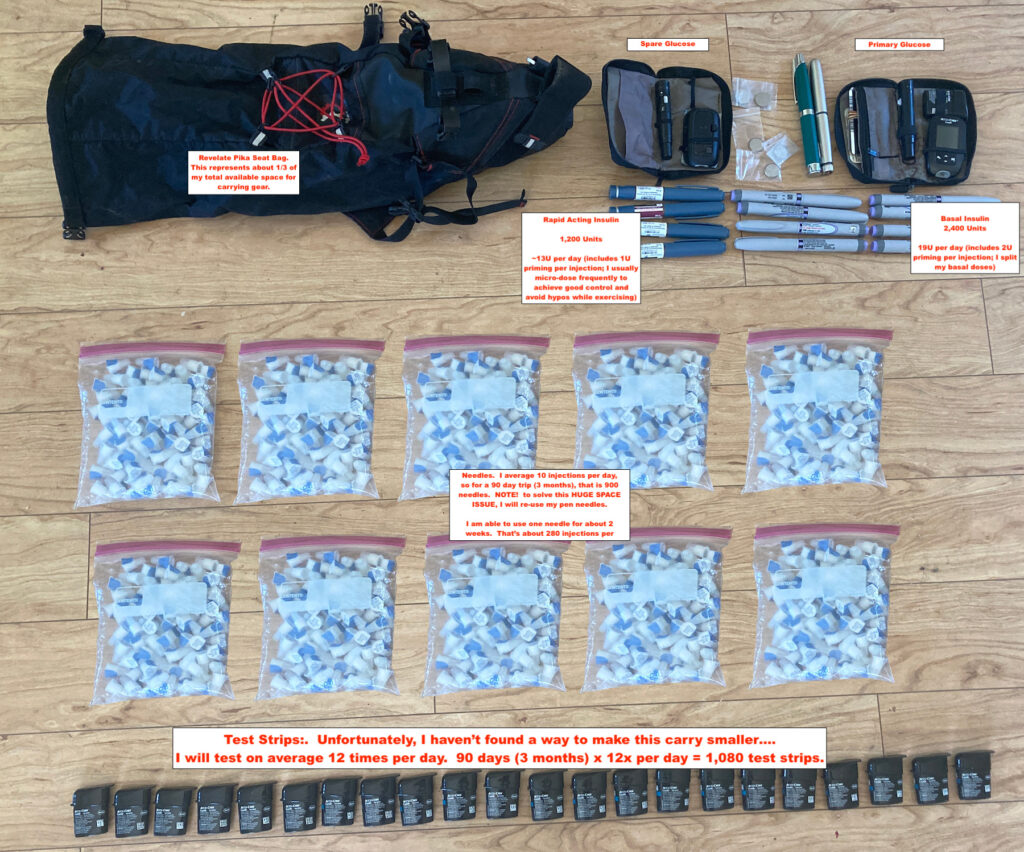

Traveling Light! All the equipment for two people riding 50 days on the Baja Divide.So, how do I carry 3 months of diabetes supplies and keep them working – even in tropical locations like Guatemala and Honduras? First, here is a photo of what 3 months supply looks like (in the upper left is a bikepacking seat bag for size reference; it represents about 1/3 of my total carrying capacity).

Here is what 3 months of diabetes supplies carried in the “traditional method” looks like. As you can see, if I followed all of the rules, nearly half of all my carrying capacity would be consumed by diabetes gear for a 3 month trip!

Here is what 3 months of diabetes supplies carried in the “traditional method” looks like. As you can see, if I followed all of the rules, nearly half of all my carrying capacity would be consumed by diabetes gear for a 3 month trip!Why would you want to carry 90 days supply?

First, let’s address the question: Why would you want to carry this much stuff? After all, there are only about 24 countries where insulin isn’t available at all (such as Somalia and Sudan). My experience thus far is limited to only 7 countries – but in each there have been major challenges getting supplies mid-trip. I have looked for insulin while bikepacking in the following countries: United States, Canada, Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, Spain, New Zealand. I have also looked for test strips in these same countries – and each situation produced major trip-slowing obstacles.

Test Strips

Each country seems to have its own meter. Not only that, but it is impossible to change the units on a glucose meter to the paradigm you’re familiar with. In other words, if you buy a meter in a country where mg/dL is not used, you will need to learn how to understand and dose for glucose measured in mmol/L. I have taken the time to familiarize myself with these units, but it adds additional burden to diabetes management. If you have serious hypoglycemia, you might not have enough mental capacity to do any extra math and get it right. Also, each meter has its own unique test strips – so you need to locate test strips which are universally expensive. In my case, that’s a minimum of $12 per day if you don’t have the help of health insurance. Finally, if you’re aiming for tight control like me, you want to work with a meter that you know is accurate – not some unfamiliar meter. This is why I carry 2 meters, all the test strips I need, and spare batteries. In Guatemala, my primary meter broke and had to start using my spare. I decided buy another to make sure I still had an extra. I found that the meter was hard to find – and when I eventually located one, it was $120USD. Luckily this meter would accept the test strips I had brought – otherwise, I would have needed to buy those too.

Insulin Type/Administration

Not only does each country have its own specific meter, but I have also found that different countries have their own injection systems. Canada, New Zealand, Australia, England (and maybe some other countries too) use insulin in a cartridge whereas Latin America and the US seem to prefer disposable pens. It turns out that the cartridge system is actually more practical for long duration travel (which I will explain later)… but unfortunately my US insurance does not cover cartridges; it only covers disposable pens. Luckily, the basic insulins are pretty much the same in each country where I have inquired; they simply have different names. If you refer to the product by the drug name (Insulin Lispro; Insulin Glargine)… vs the brand name (Humalog; Lantus) then you can usually get a pharmacist to find what you’re looking for… However, some countries don’t have some of the “fancier” insulins like Lyumjev and Fiasp…

Insulin Availability

Insulin is available in ~87% of the countries in the world – but that doesn’t always mean you can actually get it. When bikepacking, we usually try to keep our routes on trails or minor dirt roads. This means that we often avoid the “big cities.” I’ve found that in Mexico, Guatemala, and Honduras, you can buy insulin over the counter without a prescription – BUT… you need to be in a city to be able to find a pharmacy that has insulin. When they have insulin, it’s usually just basal insulin like Lantus, which is more common (lots of Type 2 diabetics will only need a basal insulin, and Type 2 is far more common than Type 1 in Latin America). Sure, this will keep you alive, but you might have to travel to multiple cities before you can find fast-acting insulin for your meals. Luckily, I’ve paid as little as $14USD for insulin pens (in Mexico)… and never more than $35USD (Guatemala) in these over-the-counter countries.

Having insulin available over the counter is FANTASTIC and I wish ALL COUNTRIES had this option. Diabetes is hard enough to manage without the extra friction of insulin availability. It turns out that in US 1, Spain, New Zealand, and Canada you need to have a prescription for insulin. This hasn’t been a big problem for me in the US – while traveling I can usually call my pharmacy and have them transfer an existing prescription (as long as I constantly keep it active by seeing my doctor every year). This was a big problem in New Zealand, however: The rules are that the prescription MUST come from a New Zealand Doctor. Since I’m not from New Zealand, this means that I can’t even see a NZ Doc; instead I would have to go to the emergency room (i.e. you need to bikepack to a city that has an ER and pay ER fees out-of pocket – not cheap!)… wait and get a prescription. When I asked in the pharmacy: “What if I ran out of insulin or my insulin bag got lost… or what if I had my insulin stolen? Could you sell it to me then?” The answer was, “No.”

I think I can survive a full day without insulin – and I’d probably make it two days… but I’m not sure how far I’d be able to ride my bike in a state of insulin-deprived ketoacidosis on that 2nd day. Without insulin, the amount of time I’d survive is shorter than how long a non-diabetic could live without water. Being dependent on exogenous insulin is far too fragile of a situation for me to rely upon the whimsical laws of a random country. If you are a non-diabetic, imagine what it would be like if you needed a prescription every time you needed to buy water – and that water was only available in specialized stores in big cities. That is why insulin needs to be available over the counter everywhere!!!

I am now in the midst of a proposed 6 month bike tour that will hopefully include 3 months in Western Africa where insulin will be impossible to source. This is what I am carrying. Temperatures have already exceeded 100F for many days. I will post an update by February 2024 if this system works for 6 months. Not pictured are spare syringes or my backup injector pen (in case of primary injector failure). I have 3 meters (two spares). 1800 test strips to test 10x per day. My insulin sensitivity has me at about 11U per day on “Hard Days” and 35U per day on consecutive Rest Days… and everything in between on medium days or single rest days. This amount of insulin should work because I will use less in countries like Spain and France where healthy low-carb food is available. Then I anticipate having to use more insulin in Africa where lower quality food choices may be the only options available.

I am now in the midst of a proposed 6 month bike tour that will hopefully include 3 months in Western Africa where insulin will be impossible to source. This is what I am carrying. Temperatures have already exceeded 100F for many days. I will post an update by February 2024 if this system works for 6 months. Not pictured are spare syringes or my backup injector pen (in case of primary injector failure). I have 3 meters (two spares). 1800 test strips to test 10x per day. My insulin sensitivity has me at about 11U per day on “Hard Days” and 35U per day on consecutive Rest Days… and everything in between on medium days or single rest days. This amount of insulin should work because I will use less in countries like Spain and France where healthy low-carb food is available. Then I anticipate having to use more insulin in Africa where lower quality food choices may be the only options available.Considering the above, I’ve decided that I need to take the following precautions when traveling:

- Carry ALL of the supplies for the entire duration of my trip (and add in extra supplies in case of flight delays).

- Put insulin, needles, and meters into separate bags on the bike (and on my person) to buffer against loss or theft.

- Put a tracker on my most important gear – the insulin and the needles. Even without a meter, I can “guess” in a pinch- but I’ll always need insulin AND needles.

- Carry some syringes as a backup in case the pen mechanism fails and I need to aspirate insulin from a broken pen.

How do I make it all fit?

Now that you know WHY I carry everything I need, let’s discuss how I make it all fit.

Saving Space by not using a pump or CGM

I used to have a CGM, and the space occupied by this device and its accompanying paraphernalia would have filled all of my bikepacking bags several times over! Each sensor comes with a huge application device – and there is no way to apply the sensor without the applicator. This makes CGM out of the question for long bikepacking trips. Similarly, a if I had a pump, I would need to change my infusion set every 3 days, meaning I’d need to bring 30 of these for a 90 day trip as well as insulin in vials… and lots of syringes as spares in case the pump broke. There are a number of other reasons why a pump won’t work for my lifestyle: so I save space by leaving it out.

Saving Space with Needles

The biggest space saver has been with the needles; you will notice in the picture above that the bags of needles take up the most space. I accomplish this by re-using my needles. This has always been “against the rules,” but I have found that I can make a single needle last about 2 weeks (about 140 injections for me) before it gets so dull that it hurts a lot. I have found that the Novofine Plus 32g needles last the longest. I have also used BD needles, but found that their 4mm x 32g needles (green cap) won’t penetrate after about 10 uses. Meanwhile, their 5mm x 31g (purple cap) needles seem to last longer – but not as many uses as the Novofine needles. By reusing my needles, I can dramatically reduce the carrying space as seen in the photo above. I’m sure to zip a couple needles into EVERY bike packing bag, in my wallet, and in my toiletries bag. If I don’t have a needle, I can’t get the insulin into my body – so it’s like not having any insulin if you don’t also have a needle.

Saving Space with Test Strips

By 2018, after a LOT of research, I finally figured out why I had so many “defective” strips – the problem made me have to carry more than double the anticipated strip usage because more than half of my strips would be bad. The thing is: this would only happen on running / aggressive mountain biking trips. What I figured out was that bouncing around test strips in loose in a vial DESTROYS THE STRIPS. I would go on backpacking trips or bumpy bike tours, and half of the strips would result in “strip error”. Since then I migrated to the Accu Check Guide Meter. Instead of packaging the test strips loose in a vial, the strips are secured with two rubber side strips that keep them from banging around and getting destroyed when you’re being active. Switching to this meter allowed me to carry half as many strips on a long trip!

Before I began using the Accu-chek Guide meter, my test strips would bang around inside the vial – and more than half of them would go bad! I’d need to carry thousands of “backup” strips. Now that I’m using the new vials (pictured) 99% of my strips are “good” even on the most rugged outings.

Before I began using the Accu-chek Guide meter, my test strips would bang around inside the vial – and more than half of them would go bad! I’d need to carry thousands of “backup” strips. Now that I’m using the new vials (pictured) 99% of my strips are “good” even on the most rugged outings.Saving Space with Insulin

I made a recent discovery which is what prompted me to write this post: I can save space with insulin too. One might intuitively think that insulin vials are the best space saver for bikepacking – but that is far from the case:

- Vials contain a lot of insulin, so once you use it the first time, the “clock starts ticking”. Vials are more likely to “go bad” – especially in rugged bikepacking environments where sanitation and refrigeration is rarely available.

- Vials are made of glass – and because they contain such a large proportion of your insulin, dropping one vial and breaking it could be devastating.

- Vials require that you carry syringes. So far, I have not found a syringe that could be used more than 5 times (plus reusing a syringe is going to be a lot worse for contaminating your already big insulin vial because the end you stick into your body is the same one you stick into the vial. Not the case with pens. This means that for 3 months, I would need to carry thousands of syringes.

Disposable pens have been a good solution for me to carry 3 months worth of insulin… except for the fact that I always run short! When I travel, the stress from being on the airplane and packing the bike makes me need double or triple my normal amount of insulin. Plus, sometimes I get stuck in “food deserts” where the only available things to eat are extremely high-insulin-burning junk food. Finally, getting bit by bugs, and getting illnesses (which seems to be ubiquitous for my travels) dramatically increases my insulin needs over baseline. Rest days (sometimes unanticipated due to weather) also force me to triple my insulin needs. I’m going to discuss this odd phenomenon in a future post.

Although I’ve proven to myself that insulin does not need to be refrigerated for periods of up to 90 days, I also know that if insulin is exposed to temperatures over 80F for too long, it will begin to diminish in its potency. Therefore, I always carry my insulin in a thermal bottle to buffer it from the diurnal swings in temperature. This can be very effective if you’ve parked your bike in the hot sun in Mexico. The surface of your black bikepacking bag can be 120F in the hot sun, but the insulin can be 60F inside the cool Thermos.

The problem with carrying a 90 days supply in pen form is that I can’t quite fit 90 days worth of pens into a single Thermos. Thanks to my trip to New Zealand as well as helpful discussion with the Type One Normal Support Group, I discovered that inside each disposable pen, there is a little “insulin cartridge” that will fit inside of reusable pens.

Here is a video on how I take apart Lantus pens, retrieve the cartridges, use them in a reusable injector, and keep track of my insulin while on long trips.

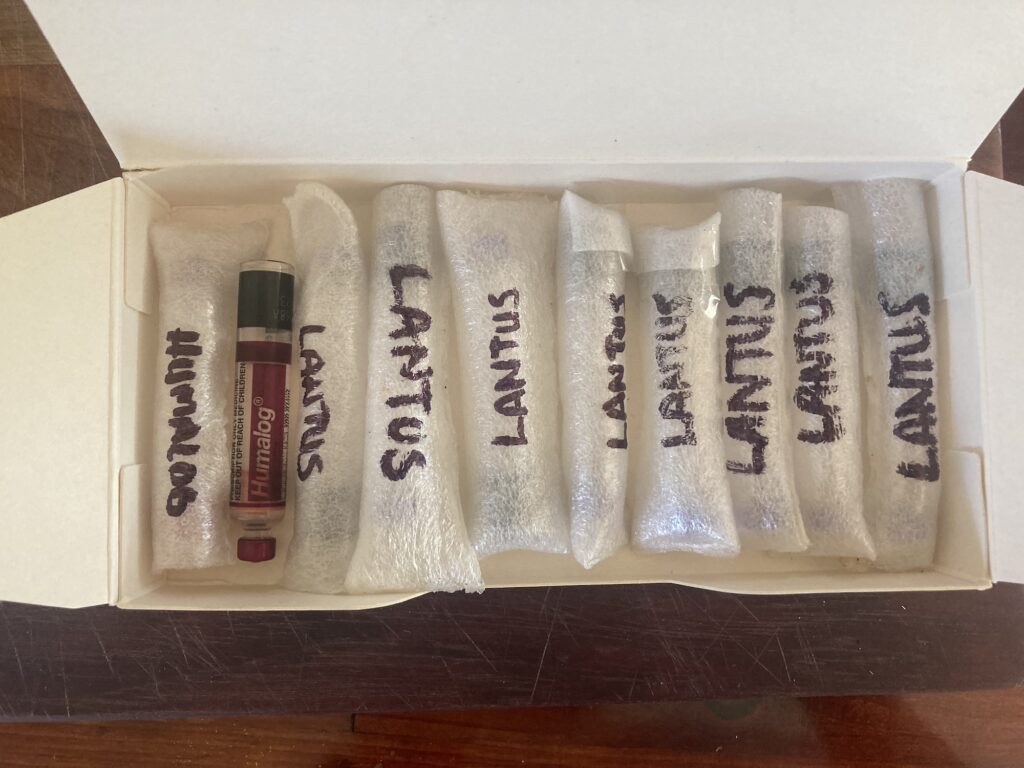

It probably seems a little silly that I’d be buying disposable pens only to break them apart and throwing away the dispenser! It turns out that my insurance will NOT cover the cartridges (the little part inside), but insurance does cover my disposable pens quite well. So, as a cost-saving approach, I’m taking apart the pens and storing the cartridges in little foam “wrappers” that I made by melting foam squares into pouches on my griddle.

Upper left: To cut open a Humalog Pen, I put my Dremel tool on the “RX” on the pen label. It’s really important where you start cutting because you don’t want to damage the glass vial inside. Next (top right), I work my way around the pen with the Dremel. Bottom Left: I stick a screwdriver in the gap and carefully pry. Bottom Right: Pop out the vial and store!

Upper left: To cut open a Humalog Pen, I put my Dremel tool on the “RX” on the pen label. It’s really important where you start cutting because you don’t want to damage the glass vial inside. Next (top right), I work my way around the pen with the Dremel. Bottom Left: I stick a screwdriver in the gap and carefully pry. Bottom Right: Pop out the vial and store! This box is a Lantus pen box that normally holds 5 pens. In the photo, you can see I have 10 cartridges in my first layer. I left one of the cartridges out of the protective foam so you could see what they look like naked in the box. If I were to pack these like sardines, I could easily fit a second layer of 10 in this box – meaning that I could carry 20 cartridges in the same amount of space that I used to only be able to carry 5 pens. WIN!

This box is a Lantus pen box that normally holds 5 pens. In the photo, you can see I have 10 cartridges in my first layer. I left one of the cartridges out of the protective foam so you could see what they look like naked in the box. If I were to pack these like sardines, I could easily fit a second layer of 10 in this box – meaning that I could carry 20 cartridges in the same amount of space that I used to only be able to carry 5 pens. WIN! Here is a pictorial summary of where I stash my various diabetes kit across different portions of the bike. The idea is that someone may grab a bag to steal it – but by having the insulin and the needles distributed in multiple locations, I reduce the risk of losing all of my insulin at once. Not shown: I also carry a kit (with a tracker) in my jersey pocket at all times.

Here is a pictorial summary of where I stash my various diabetes kit across different portions of the bike. The idea is that someone may grab a bag to steal it – but by having the insulin and the needles distributed in multiple locations, I reduce the risk of losing all of my insulin at once. Not shown: I also carry a kit (with a tracker) in my jersey pocket at all times.

Here is the rundown on how I carry the insulin. Top left: The bottle – note the contact information. Also note the wrap of duct tape – this is a “stop” to keep the bottle from bouncing out. Top right: An Apple air tag with adhesive double sided tape on one side and gaffers tape over the top to protect from moisture. Bottom left: A sock which I can get wet for evaporative cooling if temperatures go over 85F. Bottom right: mounted on bike. Note the special cage with the dial adjuster. This interfaces with the duct tape band mentioned in the first picture. Finally, as a backup, I also have an elastic hair tie around the bottle. Note that as a backup For the cage breaking (I’ve had this happen too) I also zip tie the cage to the fork twice – in addition to the bolts.

Update: Did it work?

Yes. I carried 180 days of insulin in a thermos on a bicycle – largely on unpaved roads and rocky trails from France to Ghana. The insulin I started with worked at the end of the trip – even though temperatures in Northern and Western Africa exceeded 100F on a daily basis. This tells me that Humalog and Lantus will work a long time outside of the refrigerator. I did break two of my vials in the foam wrappers. Since then, I have changed the protection from the foam to the leftover clear plastic piece from the Lantus pens. I save these now and have a large collection. I put some padded tape on the backside and can still fit just as many cartridges in my thermos. Another thing I did was put clear plastic tape over the graduation lines on my syringes. All the bouncing around would wear off the numbers and lines, but the tape prevents this from happening.

All material on this website is provided for your information only and may not be construed as medical advice or instruction. No action or inaction should be taken based solely on the contents of this information; instead, readers should consult appropriate health professionals on any matter relating to their health and well-being.

Why are you not using a CGM device that sends your glucose readings to your smart phone? something like freestyle libre 2…would save u a ton of space.

Good question. I used to have a Dexcom, and with the applicator and packaging, a two week supply would fill my seat bag. Maybe it is smaller since the G5? Anyway, for a 180 day trip… that would not fit! On top of that, CGM was not accurate for me due to rapid changes in hydration during exercise. Finally, I prefer lower tech, as the Dexcom G5 failed quite often – sensors would need to be replaced prematurely. I could carry 2 spare Glucometers – and during my 100 days in Africa, it was difficult to find healthy food most times, let alone parts for a CGM. Of course, another person may have a way to do a 190 day trip by bike with a CGM, but I present this as one possible solution.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ePnLXUcdBfc

check it out, maybe cud work. nice part is u dont need to keep checking as it gives you a warning to smartphone before the low or high.

when I found your blog I felt really grateful, and I think it is incredibly important for diabetes type 1 patients with still the desire to discover the world riding a bicycle. I will introduce my self breafly. I am Luca from Italy, I moved 5 years ago to Austria for my PhD in cancer metabolism. Before moving I promised to my best friend that at the end of the PhD we will cycle together for a long trip. Two years after I moved here, I received the diagnosis of diabetes type 1. Now, We planned to leave next January to cycle in south america and then back from the balcans to Asia. I am thinking to keep insulin for 2 months in the Frio bags but then I need to get fresh one. I am trying to figure out how to manage the insulin supply since as you posted they last only 2/3 months. How are you managing to get fresh insulin when the 2/3 months expired?

My hypothesis were: when I am still closed to Europe, just take a flight back and take some fresh insulin from home. When I will be further away I was thinking to send fresh insulin via a delivery company to some accomodation where I could wait till it arrives. what is your experience? what do you suggest?

I am really grateful for any suggestion, feedback.

thank you very much

Thanks for the message, and I am sorry about your T1 diagnosis. It is hard – but definitely shouldn’t stop you from bike touring. Today is day 113 for me on a tour. I am in Africa now, with 90-100 days to go. I cut open my insulin pens and wrapped the glass cartridges in foam. Then I put the cartridges in a vacuum bottle (thermos) I am carrying 200 days of insulin

Because I eat low carb and because I exercise a lot, I only need 15-18 units per day. On rest days, I may need 30 or 35… but on exercise days I need 12 or 13 units.

You can do it!

how is going the travel in Africa? I would have a second question regarding the potential use of a mini fridge for insulin storage that it could be charge with a power bank. have you ever tried? I saw different models online but I do not know if they could effectively work charging the the power bank with a solar panel. Thank you for your advices

The travel is going well. Today I am waiting for the wind to turn around so I don’t have to fight a headwind for two days!

Here is the deal: modern insulin is pretty hardy. It can handle temperatures up to 90F. There is now published research supporting this:

https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/998016?ecd=wnl_tp10_daily_uni_231103_MSCPEDIT_etid6022436&uac=320726BX&impID=6022436

My experience agrees. When bike touring, simplicity and light weight are two most important aspects of success. A thermos and a wet sock around the bottle use two extremely simple features of physics to keep the insulin at a safe temperature, and should work almost anywhere in the world.

Hi Brian,

What kind of thermos did you use to refrigerate your unopened supply of insulin for 3 months of travel?

Joanne – thanks for the question. Any vacuum bottle will do. I think you can see mine in the photos, but the stainless steel bottles are durable (I wouldn’t use the old fashioned glass ones). I am using a 500ml bottle because it is lighter than the 750ml bottle I used to use. Also, after cutting out the cartridges, I was able to fit in 200 days of insulin (for me). In the Sahara desert, I have placed a drymax sock over the bottle, and then I get it wet whenever I find extra water. This evaporative cooling helps the bottle stay even cooler – though I’m not certain it is necessary. I think another key component is using the smaller 3mL cartridges as opposed to the typical vials which require syringes. I know another bike tourist who has had 3 of those vials go bad. Here is why not to use those vials:

1 – you must inject air whenever drawing from them. This could cause contamination. Meanwhile, the cartridges have a plunger so theoretically you’re never putting stuff into them, only out.

2- if you break a vial, you have lost a lot more insulin than if you break a cartridge.

3 – in a pinch, a cartridge can be reused. Just take insulin from any source, aspirate, and refill the cartridge. You can even use a disposable pen to refill a cartridge directly. I did this last week when two of my cartridges shattered due to extremely rocky (and fast) downhill mountain biking.

Thanks Brian

Love this Brian! As a type 1 diabetic myself, I found a lot of these tips (especially the cutting down pens) very useful! I am wondering what supplies you carry if you have and hypos when riding? I’m sure you’d always be carrying something for emergencies?

Thanks for your comment, Fraser – The cutting of pens has been a game changer for long trips! However, if you have access to the cartridges, that is of course a better solution. I don’t carry Glucagon simply because so far there hasn’t been an issue that couldn’t be remedied with sugar. I buy a small pack of sweets for emergencies, but even a small knob of bread will do. I find that because I generally eat low carb, just a couple raisins or a tiny crumb of bread will get me out of a hypo – often sending me too high if I also stop exercising. If I know I’m going to be doing harder exercise in a remote area, I’ll lower my basal and carry more carbs just to be safe. When I travel with my wife, I don’t carry anything special because she fuels almost entirely on carbs, meaning I have a ready supply thanks to her!