John Muir Trail

Although light, the snow had been falling for hours. Janet and I were trudging up the first of two 12,000′ passes in knee deep powder and white-out conditions – no sign of a trail. Our average speed had been 1 mile per hour for the past 3 hours. We had 10 miles left to escape to a trailhead… all we had left was a handful of trail mix, a wet tent, and eight and a half hours of daylight. Out of the blue, Janet had an announcement to make: “I never want to climb Mount Everest.”

2015 has seen an unprecedented interest in backpacking. In prior years, about 300 people per year would take out permits to attempt the full Pacific Crest Trail (PCT). For 2015, it is estimated that about 3,000 people will attempt the full PCT trail – a 10x increase! I’ve been on the trail a few times this year, and from talking to people, the consensus opinion is that the surge of interest is related to several recent books-turned-movies: “Wild,” “Mile, Mile and a Half,” and “A Walk in the Woods“. These movies have brought backpacking into the mainstream eye of the public.

Sections in this Post

Why We Went

Planning your Trip

Our Story

We first met Jae-hoon and Taewoo at Muir Pass. We were traveling at the same speed, so we saw them each day after that. They flew to the United States from South Korea solely for the purpose of hiking the John Muir Trail! What made them decide to do it? The movie “Wild.” Here, they are pictured at Pinchot Pass

Why we went

Our journey began when my former co-worker sent me a text message on February 1, 2015 saying that she wanted to hike the John Muir trail. She asked if Janet and I wanted to go. Although an avid hiker, my former co-worker had never been backpacking. She is pretty well known for making April Fools pranks, so I wrote her back saying that April 1st isn’t for another 2 months. After some back and forth, it became clear that she was serious – she had “just seen a movie about the JMT.” I told her we couldn’t go, but a seed had been planted. Two weeks later, our friends Peggy and Mike asked if we wanted to hike the JMT with them. This was too strange: all these friends were suddenly asking if we wanted to go backpacking with them. It turns out that they had just seen one of the movies mentioned above (Mile, Mile and a Half). I called my co worker to verify: The same movie had inspired her to hike the JMT. This must be a very inspirational movie, I surmised! The next thing I knew, Janet started getting interested and she was watching youtube videos, and doing permit, and resupply research.

The two most difficult parts of hiking the John Muir Trail are obtaining permits and determining your resupply strategy. I love the Sierra Nevada in the fall, so I was secretly pleased that our permit for earlier in the season failed. The fall colors just add to the already beautiful nature of the mountains.

Due to the unprecedented interest in the JMT for 2015, we were unable to secure permits until fall. In my opinion, this was a good thing: weather in September is usually some of the most stable of the year, temperatures are generally cooler, bugs are fewer, and crowds are low.

*In case you are wondering, neither my former co-worker nor Peggy and Mike were able to make it, but Peggy and Mike would later drive around the range to be our resupply.

Planning your trip

Here is everything you need to know about the most important aspects of hiking the JMT. This blog can not cover the breadth and particulars of “how-to” backpack, so all this info is JMT specific.

1) Permit – Getting a permit to hike the JMT is by lottery. You apply 182 days in advance for your permit (via fax, phone, or snail mail), and they let you know if you have been accepted. Phone and snail mail are impractical; Fax is the best. Here is the Permit application page. The cost is $5 per person, plus a $5 transaction fee. Here is where you can download the permit reservation form to mail or fax. You can also try your luck with a day-of permit reservation. Early or late season, this could be feasible. In my younger days, I didn’t understand why permits were necessary; I thought they were a nuisance. After running portions of the JMT this summer (and seeing people every 15 minutes or so), I now understand and very much appreciate the permit system. Even with the restrictions, in the summer, the John Muir Trail does not feel like a wilderness. By the time of our trip (late September), we’d see no more than 4 people the entire day on most sections (except near Mammoth and Yosemite Valley). On some days, we hiked nearly the entire day without seeing anyone. Here is the NPS info page about WHY you need a permit.

Getting a permit for late season rewarded us with wonderful fall colors, cooler temperatures, and no bugs. There would be one drawback, though… Snow!

2) Resupply – There are quite a few resupply options, but most of them are not fun or inexpensive. The most comprehensive list of options I found are listed here. Rather than reinvent the wheel, I’ll direct you to a website that has cataloged the conventional as well as the less common methods of resupply (Like rental llamas carrying your gear for you)! Carrying more than 6 days of food (~9 lbs for most people) is not very enjoyable. The resupply is important and requires advance planning. Be mindful of the open dates of the main establishments. Red’s meadow closed the day after we picked up our resupply, Vermillion Valley Resort was open – but it was a ways off the trail, and only 2 days after our Red’s Meadow resupply. Muir Trail Ranch closed early this year – perhaps due to the fires. The unconventional methods – either by pack stock or friends hiking in can work well (and be staggered more efficiently mile-wise).

Our resupply strategy had been to hike 4 days, resupply at Red’s Meadow, hike 8 days, resupply by friends who hiked in over Kearsarge Pass, hike 3 days. Our resupply strategy went bad when we encountered this snow on the day our friends were supposed to hike in.

3) Food Storage – I’ve studied the bear canister map requirements carefully, and determined that the only legal way you can travel the JMT without a canister would be if you could make it to Red’s Meadow on the first day (about 60 miles!) This would be a very difficult day for most people. Therefore, you’re going to absolutely need to have a bear canister. Although we did not encounter any bears, plenty of people have – and the intention of the canister is to re-train the bears to stop seeing human food as an option. Using a bear canister is like taking the full-course of antibiotics: if everyone follows the rules, we won’t get resistant strains of bacteria. Likewise, if everyone had a bear canister, the bears would give up on human food.

On the way up to Donohue Pass. Donohue pass is where you exit Yosemite. Current regulations restrict this pass to 45 people per day.

4) Round Trip transportation – During the summer, it is fairly easy to set up a self shuttle: Drive to Whitney Portal (or Yosemite Valley) and take a combination of YARTS (Yosemite Valley to Lee Vining). and Eastern Sierra Transit (Lone Pine to Lee Vining). If you drive to Whitney and leave a car, you will have to find your way to Lone Pine. I ran down the hill, but hitchhiking is a common option. In the off season, YARTS does not run every day – so we found ourselves hitchhiking from Lee Vining to Yosemite Valley. There were 4 of us hitching, and we were all picked up (separately) within 4 minutes. Of interest, we were picked up by a European couple (French)… The people we talked to later also received rides solely from Europeans.

I ran from Whitney Portal back to our hotel in Lone Pine. On the way, I passed this rock. The road to Whitney portal is quiet and enjoyable enough for a run – though hitchhiking would have also been very easy.

5) Guidance – The John Muir trail is very well signed in most places. Nevertheless, your enjoyment will be greatly increased by having a good map. There are many guides out there, but if you’re looking for the best map in the easiest to use format, I highly recommend the National Geographic John Muir Trail Map. When we got our permit, we were given several pages about the rules for Inyo National Forest (because they differ from Yosemite’s rules). We cross-referenced the 3 page handout, and found that every “no camping” spot mentioned was also detailed on the National Geographic map. We took photos of the hand outs and discarded this redundant paper information before the trip. Common campsites are detailed on the map, making it easier for your to plan the day’s mileage. This map was outstanding, and did not let us down once.

Our Story

The first few days of our trip, we saw the most people. We spent the night in the backpacker’s camp (between the Awahnee and Happy Isles) for $6 per person. You can only stay here if you have a wilderness permit – and you’re only allowed one night before and one night after your trip. From here we ascended amongst a few small groups up to Sunset camp. The ranger had warned us that there is no water at Sunset camp – so we carried extra water bottles up the big initial ascent. Upon arrival, we were ?happy? to discover that there was indeed water flowing in a small ditch. Sometimes, I feel like people say there is not water in places when there isn’t more than a million gallons of water. The fact is, we only need a few liters, so even a puddle would suffice. There was plenty of water late season after many years of drought throughout the entire trail. The longest stretch we encountered without water was only 5 miles.

I was eager to complete the first two days; I figured the trip would “really begin” once we crossed Donahue Pass. That’s where I felt the good scenery would begin. Indeed, if you strictly follow the JMT from Happy Isles to Tuolumne, you’re going to be in the forest with few views after you pass Vernal falls. Some hikers take the Clouds Rest trail as a more scenic alternative. I would probably do this next time myself.

Prior to the trip, I believe I had the notion that the Sierra High Route had better scenery than the JMT. The spectacles along the JMT were just as fantastic (and sometime better) than the high route. In this picture, for example, the high route follows the base of Mt Ritter / Banner. Unlike the SHR, the view from the JMT lets you take in Garnet Lake with the mountains behind… spectacular!

Leaving Yosemite, we saw far fewer people. The numbers did not increase until we neared Mammoth (it happened to also be a weekend, otherwise, we probably would have only seen a few people here too).

The pass just South of Thousand Island Lake. We found Ruby and Emerald lakes to be exceedingly beautiful as well.

Usually, after a backpacking trip, I feel like I deserve to “treat” myself. When I pare down my life to a simple way of living with few material items and simple food, I feel like I have “earned” a little special treatment. Nevertheless, by day 4 – when we arrived at Red’s Meadow, it didn’t really feel like time for a treat. The travel had been pretty easy, and we’d had plenty of food so far. I almost wished we had brought less food for the first 4 days so I would have been dreaming of their ice cream and burgers. As it turned out, the experience was quite ordinary. With full bellies, we picked up our 8 days worth of food, and I was glad to find that the bagels we had shipped ourselves were already moldy. We tossed them; it seemed like we had WAY too much food for the next 8-1/2 days.

Our first night after the resupply was at beautiful Virginia Lake. This lake is gorgeous from all angles – but on this night we were treated to a double sunset show AND the blood moon. Perfection!

The days and miles ticked by with great scenery over Silver Pass, Selden Pass, and Muir Pass. Each day was overcast and threatening, but I downloaded a weather forecast that said the next few days would be OK. Precipitation wasn’t predicted until the day we planned to ascend Muir Pass.

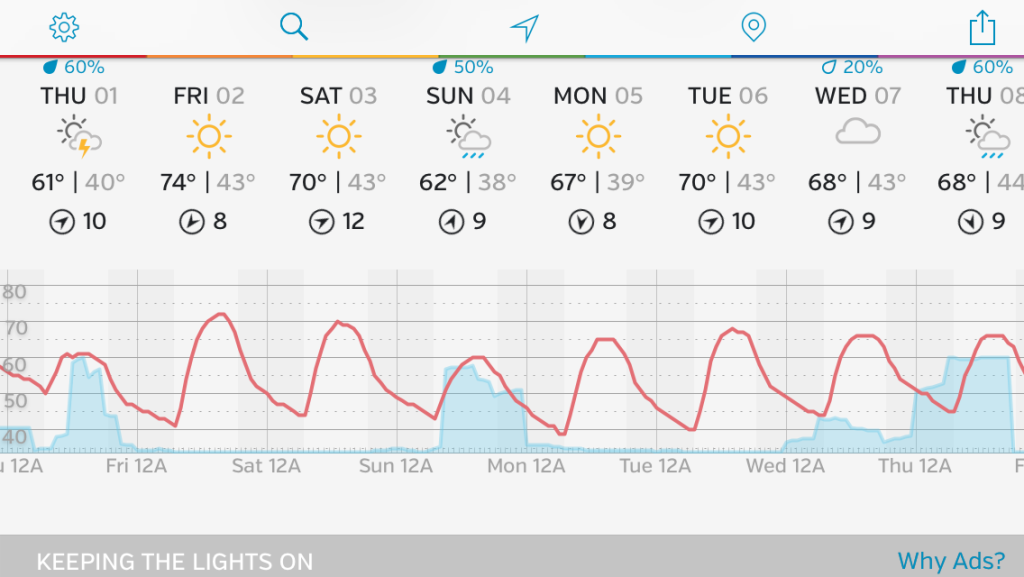

The weather report I obtained. It would be correct for Thursday the first and Sunday the 4th. A surprise, however, for Monday the 5th awaited us…

Precipitation arrived as predicted on the 1st of October. Even I was surprised how quickly the weather turned. I knew the Muir Hut (at 12,000′ – only a mile away) would provide good shelter if things got worse. I decided to fill all of our water bottles (in case we had to spend the night), and hurry to the hut so I could drop my pack and help Janet with hers. I left my pack in the hut amongst two guys from South Korea, and ran towards Janet in worsened, biting cold, white-out conditions. Apparently, she had decided to move quickly too – because she was only a few hundred feet behind me! She carried her pack to the top because it was “keeping [her] back warm.” Inside the hut, there were four of us now: Me, Janet, and the two guys from South Korea (Jae-hoon and Taewoo).

I was secretly happy that we had stormy weather when we reached the Muir Hut. I was thinking it would be cool to spend the night in a “cabin” with the storm blowing outside. In the end we carried on because we wanted to stay on schedule – but we spent two hours waiting for the snow to abate.

After a long cold descent to LeConte Meadows, and a chilly, dank morning, we began to thaw and enjoyed superb (albeit cold) weather for the next two days. We managed a double-pass day (Mather and Pinchot), and were in heaven with the beautiful autumn scenery. To my surprise, we had been forced to ration our food for the last several days. We had packed nearly 3,000 calories per person per day, but we were eating it more quickly than planned. By this time, we were eating severely restricted meals. I had prepared for this by carefully gaining about 10 pounds of excess body weight (mostly through the help of tasty barrel-aged beers). The body always seems to balk about using fat reserves as opposed to new food, so I was starting to feel just a little un-easy about our situation.

Based on our increasingly antiquated weather report, we figured we were in for some weather on the 4th. Snow arrived as expected, so we decided to take a short day and end at Rae Lakes. The plan was to meet our friends near Bullfrog Lake for a resupply the next day, and since our weather report had been accurate thus far, we assumed that the 5th would be a sunny make-good-miles day.

As the snow continued into the night, I repeatedly sloughed it off the 3 season tent. Our tent is light-weight, and not designed to bear the weight of heavy snow. Janet managed to sleep well citing the facts: “We can’t do anything about it, so why worry?” Knowing that we were 12.7 miles and two 12,000′ passes from a trail head, and that our average pace was about 1 mph – with only 12 hours daylight, I began to consider our predicament. We were nearly out of food, and we were carrying what most people would consider to be “inadequate attire” (i.e. shorts and running shoes for me). I kept hoping for the snow to stop. I hoped at 12am, I hoped at 2am, I hoped at 3am… It finally stopped for 2 hours at 4am – and then resumed. I knew those 12,000′ passes were going to be deep in snow…

I still figured that we would have clear skies on the morning of the 5th – but we woke to continued snow and surprisingly dark and low clouds. We packed up all the wet gear and headed off, making clumsy progress through the snow; the trail non-existent.

I watched our progress on the GPS. We were moving more slowly than I had anticipated. I started calculating that we’d have about 2 hours hiking in the dark. It was difficult enough to find the trail in daylight: We were finding the “trail” by using my Garmin Epix GPS. I had loaded an OSM file that has a very accurate map of the JMT. You can determine your position within a few feet, so we were able to navigate quite accurately along the trail. Soon we came across the two guys from South Korea. They had no idea where to go without a trail – so they were just standing by where they had camped. We were extremely happy to see them, and they were happy to see us. Now, none of us felt “alone.” There was still a lot of work to do, though. I reassured them that my GPS could help us find the way out of there. They were overjoyed to know that we had a means to escape. None of us really wanted to spend another night in wet tents. We ascended into the dark clouds under white-out conditions, with no trail to follow.

White out conditions with only the GPS for guidance. You can see a couple rocks faintly pointing out of the snow.

We hurried up Glenn Pass as best we could. The snow drifts were increasingly deep near the top, and the wind was strong, spinning snow from the ground into the air. On the South side of the pass, we got some relief from the white-out and the wind.

Our spirits lifted as we descended. Part of me was enjoying the beauty of the snow. Also, I was really glad that my feet didn’t feel numb. They were definitely cold in the Hoka Rapa Nui 2 shoes (with plastic bag liners), and they managed to survive 10 hours of walking in the snow. Janet reported that her feet were equally cool (but not frozen) in her LaSportiva Wildcat shoes. I refrained from getting too excited, though, as I knew we had another (nearly) 12,000′ pass to cross: Kearsarge. We hurried along and yelled towards Bullfrog lake in the unlikely event that our friends had actually hiked in with the resupply. Not hearing anyone yelling back satisfied us that they had made the smart move by not coming.

Climbing over Kearsarge was steep, but in our memories, it was going to be 12,000′. When we got to the top, we saw that it was only 11,760′. That lower elevation helped, as each vertical foot was laborious in the ever deepening snow.

In previous days, Janet had been experiencing a lot of foot pain that had been slowing her down. Today, she moved adroitly citing the extra cushion provided by the soft snow. She also quipped that her foot did not hurt today (because she had been “icing” it all day). We finally made telephone contact on the East side of the ridge. Our friends Dave, Mike, Peggy, and Nancy had all generously come to do the food drop – and they were waiting for us at the Kearsarge trailhead. With renewed interest, we sped down the hill as fast as we could. The snow became shallower and more benign; eventually slushy. We saw our friends in the parking lot. They had done their own hike(s) in the snow, so they were wet and cold – but patiently waiting for us. We were very grateful to see them; The chances of anyone being in that slushy parking lot late in the afternoon was quite small. I was dreading a 13 mile walk down the road to Independence.

**Discussion**

Looking back at a potentially dangerous situation, I can’t say that I would have done anything differently. You assume a certain amount of risk when entering the wilderness – and that risk is heightened early/late season due to the potential of snowfall. We had a weather report which was aging, but there is no way of getting an update unless you’re carrying a satellite phone/messenger. Even if we were to have had a report, we later found that the forecast was extremely fickle these two days – and varied highly by location. I can’t say we would have changed our decisions based on such conflicting reports. We may be criticized for not having proper footwear for the snow on an October backpacking trip, but our feet were never numb the entire day. We were also carrying an ACR PLB, which made me worry less about a true emergency. I will say to die-hard map-only users that a GPS device is definitely an excellent safety tool in these types of conditions. Finally, although we were very tight on food, humans can go many days without food, and we were never more than 2 days away from civilization. We’re slightly disappointed that we did not finish the route – but that makes a great excuse to go back!

**UPDATE** ON October 1, 2017, Janet and I went back and completed the trail. You can see both trips combined in the map below.

This is the map for the entire route discussed in this post. To Export GPX files, click on the three horizontal bars in the upper right hand corner of the map and select Export selected map data…

To see full screen, click here (opens in new window)

You were hiking in shorts? And you had no pants in white-out deep snow conditions? Did I read this correctly? Dang.

California, all the way! Seriously, though, I borrowed a pair of Janet-size tights from Janet. This resulted in some not so casual downward glances in the parking lot, as well as some choice comments.