Type 1 Diabetes FAQs – What do you Think you did to Cause your Type 1 Diabetes?

Here is a conversation that I’ve had quite frequently. I’ve had many variations of this conversation, but they almost always bring up my healthy diet and “excessive” exercise:

Person: “So, what do you think you did to cause your diabetes?”

Me: “There is nothing I could have done differently. Type 1 is an autoimmune disease1; the cause is unknown”

Person: “I know, but I mean… You eat so healthy.”

Me: “It has nothing to do with that; Type 1 is different fr…”

Person: “It’s just so strange, I mean you exercise so much!”

Me: “I think you’re thinking of type 2 diabetes…”

Person: “Well, don’t you think that all of your excessive bike riding caused it?”

Me: No… Let me explain…

Usually, eyes glaze over when I begin my explanation, so it’s probably not an interesting topic for everyone. Although type 1 diabetes is a very rare disease, I believe that educating people about its possible origins is potentially beneficial. The benefit of this education comes from helping others correctly identify this potentially lethal disease more quickly and from knowing how to better interact with existing type 1 diabetics.

What really causes type 1 diabetes?

First, let’s answer the question that I get so frequently about my “excessive” bike riding. It’s Tour de France season, and these guys ride bikes a lot, which would make them good examples for finding type 1 diabetics if this theory were correct. Below, I’ve made a list of all the Tour de France riders who have developed type 1 diabetes as a result of their excessive bike riding:

If I left anyone out, please let me know in the comments below.

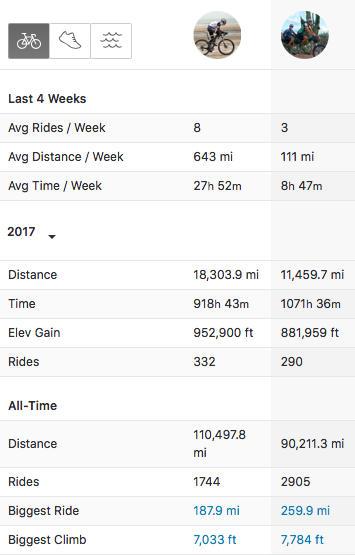

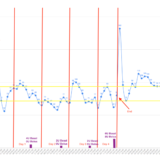

By the way, I ride less than these Tour de France guys as well. Because it was easily accessible, I grabbed the 2017 data from Laurens ten Dam (a well known TDF racer). I decided to compare the 2017 data because that was a big year for me:

Laurens on the left; me on the right. I ride a lot less than a typical TDF rider – so I doubt that I’m overdoing it. My ride time is the only 2017 stat that is higher – and that is probably because I’m going a lot slower.

Hopefully this data solidly answers this question – “excessive” bike riding does not cause type 1 diabetes.

Confusion about the types of Diabetes

Unfortunately, our society is plagued with what people call “an epidemic” of type 2 diabetes. Personally, I don’t like to use the word “epidemic” because it connotes “disease.” I am not in agreement with the assertion that type 2 diabetes is a disease, but rather it is a symptom of some other thing gone wrong (most likely dietary/lifestyle choices)2. Admittedly, we still don’t really know what causes metabolic syndrome (aka type 2 diabetes). We do have some ideas about the causes of metabolic syndrome, which you probably already think you know: Unhealthy diet and lack of exercise. Because of the “epidemic” status of this condition, that is what people are exposed to when they hear the word “diabetes.” If you watch any television, you see that so many of the commercials are related to type 2 diabetes. Type 2 is completely different from type 1. In some ways, it nearly the opposite condition in fact. As a result of these ads and commercials for the ever expanding variety of drugs for improving type 2 diabetes symptoms, most of what people think they know about “diabetes” relates to type 2.

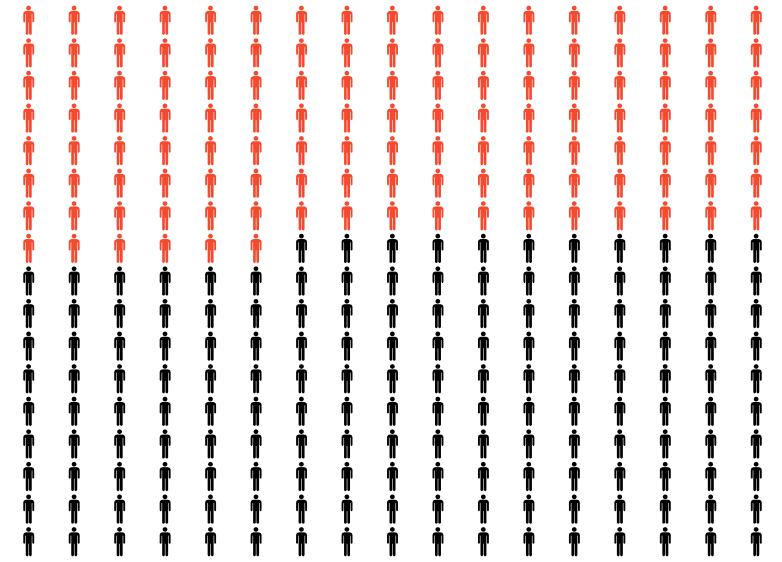

How likely are you to meet a type 2 diabetic?

Here is how often you will encounter a Type 2 diabetic in America. I have combined both full-blown Type 2 with what people are calling “pre-diabetes.” Note that the numbers are actually even higher than this because another 10% have undiagnosed type 2 diabetes. Furthermore, metabolic syndrome (type 2 diabetes) has begun long before pre-diabetes is diagnosed meaning that by the time you’re starting to show impaired glucose tolerance, you’ve already had several years of metabolic imbalance.

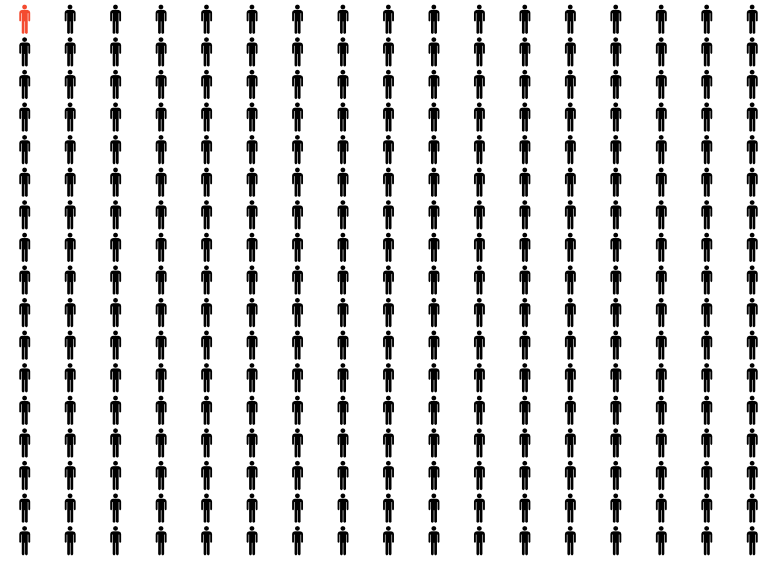

Conversely, how likely are you to meet a type 1 diabetic?

Here is how often you will encounter a Type 1 diabetic in America. That lonely little red guy in the upper left hand corner.

This is a big part of why the confusion exists. Both of these conditions have the same name – even though they have completely different causes. As you can see from my infographic, type 1 diabetes is a very rare condition that is easily confused with a very common one.

Why do these two conditions have the same name?

Back before we had fancy ways of testing all sorts of physiological parameters, both of these maladies had one big overt symptom in common: Sugar in the pee. I’ve oft read that doctors would taste the pee of a patient for sweetness to confirm a diagnosis of diabetes (not sure if this is true). The word “diabetes” comes from the Greek word “diaphanes.” That word has a modern English equivalent “diaphanous,” which you may know means “to pass through.” In other words, the sugar/carbohydrate that you eat (or sugar that your body manufactures) is passing through the body and into the urine. This same thing happens in both type 1 and type 2 because the blood sugars are so high that the kidneys start doing a job they were never intended to do: Filter out glucose (sugar) – making you pee out all the food you eat.3 Back in those days, both conditions appeared to be similar on the surface: Sugar was passing through into the urine.

From the beginning of time up to less than 100 years ago, this all must have been very confusing because some people would die from this condition right away (those were the type 1s who were making very little if any insulin). In this group, one would die between 3 weeks to 3 months post-diagnosis. In the other group, people would have minor symptoms and could last for decades with the condition (these are the type 2s who initially were making too much insulin, but eventually their pancreas could no longer keep up with the high demand). Eventually we figured out that these two conditions have very different causes, but the name “diabetes” stuck to both. Almost as an afterthought, the “type 1” and “type 2” designations were added. Since then, we’ve also added “gestational diabetes,” “LADA diabetes,” and “MODY diabetes”4 to describe conditions that share the same outward appearance (high blood sugar) – but all of them have completely different causes.

If you didn’t eat too much sugar, what caused it then?

This is where I’m going to let you down, and why I’ve saved the punch line for the lower portion of the post. The answer is: No one knows. All I have to share are the leading theories.

We develop theories about type 1 diabetes by looking at who gets it, when they get it, what’s different about their bodies, and we investigate what these people have in common. Here is the list of things of the leading theories:

-

The “It’s genetic theory”

This is a compelling theory that does have some weight – but it does not explain the entire story. An easy way to dispel the notion that type 1 diabetes is entirely genetic is by looking at identical twins who have the exact same DNA. If one identical twin has Type 1 diabetes, the other twin “only” has a 38% chance of developing type 1 diabetes.5 That is still a pretty high chance, but it does not provide a fully genetic basis for type 1 diabetes. If it were purely genetic, you’d expect the correlation to be in the upper ninety percent. This does suggest that there is at least a partial genetic component to the development of type 1 diabetes. In fact, many genes have been identified as risk factors for developing type 1 diabetes. Don’t worry if you have the genes, though, because even if you have them, it doesn’t mean you will get type 1 diabetes.6. In fact, many of the people with a high genetic risk profile for type 1 diabetes never develop the disease.

-

The “Molecular Mimicry theory”

If you haven’t studied much biology, an easy way to visualize this theory it to think of your cells like one of those puzzle ball toys pictured below. This is a gross over-simplification, but imagine that one day you are exposed to a virus or a bacteria – and that microbe has a piece on it that looks like one of the star shaped puzzle pieces in my picture.

Let’s say the star shaped piece is an invader. The immune system attacks the star-shaped virus / bacteria and then it remembers what it looks like so it is easier to destroy next time it comes along (this memory is why you don’t usually get the same cold twice and how vaccines generally work). Now imagine that the star shaped puzzle piece just happens to look a lot like part of your pancreatic beta cells. In this case, your immune system sees these cells of the pancreas as invaders and it destroys them. I personally believe this theory has a lot going for it. Anecdotally, many type 1s in various groups that I’m a part of often mention that their type 1 diabetes diagnosis was preceded by a significant gastrointestinal illness. Furthermore, some of the research supports this7. If you read my citation, however, you will find that there is not enough evidence to place the blame entirely on viruses, so again, we don’t have a single smoking gun.

Think of your cell like one of these puzzle toys; the star shaped piece can only fit into the star shaped hole. Everything that comes into the cell has a certain shape – and it cannot get in if it doesn’t match.

-

The “Hygiene” Hypothesis

One thing that researches have noticed has been the uneven geographical distribution of type 1 diabetes.

In the hygiene hypotheses, we assume that people closer to the equator are exposed (while growing up) to more viruses and bacteria. This somehow prepares their immune system to not be auto reactive. The difference between countries is huge: For example, if you live in Finland, you’re 576 times more likely to get type 1 diabetes than if you live in Venezuela or Papua New Guinea8!

Geographical distribution of type 1 diabetes. These are VERY significant differences between the countries with the most and least type 1 diabetes! In general, the closer you are to the equator, the lower the chance that you will get type 1 diabetes. There are a couple of exceptions: Saudi Arabia, and Sardinia. Three theories have emerged from this observation: The Hygiene hypothesis, the Vitamin D hypothesis, and the affluence hypothesis.

-

The “Vitamin D” Hypothesis

If you look at the image above, you can see that in general, the areas that get more sun have less diabetes. Within the United States, Washington State has higher rates of type 1 diabetes compared to more Southern states. Most people already know that the skin can produce Vitamin D when it is exposed to sunlight9. Moreover, upon diagnosis, many type 1 diabetics are Vitamin D deficient10. I find two problems with this theory: There could be another explanation for the Vitamin D deficiency. We cannot say what came first: the deficiency or the diabetes. Type 1 diabetics are often deficient in other vitamins and minerals such as magnesium and potassium. For example, because of the lack of insulin, potassium cannot enter cells. The other problem with this theory is: How do we explain the higher rates of type 1 diabetes in sun-washed Sardinia and Saudi Arabia? In spite of my doubts, there is a body evidence suggesting an improvement in glycemic control when patients supplement with Vitamin D.11. For this reason, I supplement with Vitamin D myself – it is the one supplement that I use (besides injected insulin of course!)

-

The “Affluence” Theory

This is somewhat linked to the hygiene hypothesis in that affluence tends to be linked with a lower exposure to microorganisms. Furthermore, affluence patterns seem to match the geographical distribution (considering the outliers of Saudi Arabia and Sardina). The question of the connection between affluence and type 1 diabetes has been asked in the literature12. The problem with this theory is that not all countries keep good records of the type 1 diabetes cases. Also, having traveled in some of the countries with very low rates of type 1 diabetes, I have taken a cynical look at this theory. As I have explained, type 1 diabetes usually kills swiftly. A young, untreated person who is on the brink of diagnosis usually only survives a few weeks to a few months. Due to the larger pancreatic mass, a person diagnosed as an adult can sometimes live a little bit longer. Eventually, the pancreas gives its last gasps, and a person with zero insulin in their body can only survive a day or two. Having visited some of the medical facilities in Peru and Mexico, it seems very likely that I would not have received a proper diagnosis prior to expiring. In fact, I believe that my type 1 diabetes began while I was in Peru – but in the first doctor visit, I was sent to a “miracle worker,” and in other subsequent doctor visits, no one ever thought to draw blood to discover the cause of my symptoms. Now that I know what high blood sugar feels like, I’m fairly certain that diabetes was the cause of the overwhelming fatigue, cloudiness, and depression I felt near the end of our time in Peru. As you can see, it is possible that the geography of diabetes may simply be related to the reality that in poorer nations, type 1 diabetics may quickly die before they ever get a chance to be diagnosed. This may strongly influence the reported statistical occurrence of this disease.

-

The “Stressed Beta Cells” Hypothesis

. This is a newer theory, and it is actually supported by some evidence. I have chosen to save this one for last because I think it could cause some confusion in readers. As I said earlier, eating too much sugar does not cause type 1 diabetes. In spite of that fact, there is evidence to suggest that eating could speed the progression towards type 1 diabetes13. This was a big study of 1,893 children who were genetically at high risk for type 1 diabetes (see genetic link above). One weakness of this study is that the sugar consumption values were self-reported. Nevertheless, the study did find that sugar consumption may exacerbate the late stages of type 1 diabetes development. It is important to remember, however, that type 1 diabetes had already developed – so sugar isn’t really a cause, but an accelerator. We already know pretty well that high blood glucose levels are toxic to beta cells, so this finding definitely makes sense. Of course, properly functioning beta cells should be capable of stabilizing blood glucose levels suggesting that the lack of beta cell function precedes the sugar toxicity. Even if the beta cells are under stress, though, why would the immune system be attacking them? A relatively recent review suggested that protein mis-folding in “stressed” beta cells may trigger abnormalities that make them targets for the immune system.14 Remember that puzzle ball example above? Imagine if stress caused the shape of one of the proteins to change from a square to a star. This may look like an invader to the immune system and cause an immune attack. This is a gross oversimplification of the cited paper, but hopefully it helps you conceptualize the idea.

I think we can safely say that the cause of type 1 diabetes is multifactorial, with the strongest influence being genetics. It is worthwhile to continue investigating the cause(es) because this knowledge may help determine possible medical interventions to prevent the disease prior to its development.

References & Footnotes

- Note: No, it’s not an autoimmune disease like AIDS (many people have tried to make this comparison). The “AI” in AIDS means “Acquired Immune” not “Autoimmune”

- Reference: Diabetes is not a disease of blood sugar, Ron Rosedale, 2007, https://www.diabeteshealth.com/diabetes-is-not-a-disease-of-blood-sugar/

- Note: People often ask why type 2 diabetics are overweight if they are also peeing out their food. This is a complicated issue that I will discuss in another post. To simplify, insulin can be considered as the “storage hormone.” This means that it helps you take energy from your bloodstream and put in into muscle cells, fat cells, or liver storage (glycogen). Remember that the hallmark of type 2 diabetes is an overproduction of insulin. Note that your muscles cannot stockpile surplus energy. Furthermore, the liver has a limited storage capacity (though you can start storing fat inside your organs, including your liver). So, if neither the muscles nor the liver can take on any more energy, where does it go when there is a lot of insulin floating around? To the fat cells.

- Note: As of this writing, there are 14 types of MODY diabetes.

- Reference: The Genetic Architecture of Type 1 Diabetes, Samuel T. Jerram and Richard David Leslie, 2017 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5575672/#B1-genes-08-00209.

- Reference: Genetics of Type 1 Diabetes, Andrea K. Steck1, and Marian J. Rewers, 2011, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4874193/#S13title

- Reference: Viral Trigger for Type 1 Diabetes, Christophe M. Filippi and Matthias G. von Herrath, 2008, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2570378/

- Reference: List of countries by incidence of Type 1 diabetes ages 0 to 14, https://www.diabetes.org.uk/about_us/news_landing_page/uk-has-worlds-5th-highest-rate-of-type-1-diabetes-in-children/list-of-countries-by-incidence-of-type-1-diabetes-ages-0-to-14

- Reference: Vitamin D: The “sunshine” vitamin, Rathish Nair and Arun Maseeh, 2012, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3356951/

- Reference: Significant Vitamin D Deficiency in Youth with Type 1 Diabetes, Britta M. Svoren, MD, Lisa K. Volkening, BA, Jamie R. Wood, MD, and Lori M.B. Laffel, MD, MPH, 2010, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2635941/

- Reference: Glycemic changes after vitamin D supplementation in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus and vitamin D deficiency, Khalid S. Aljabri, Somoa A. Bokhari, and Murtadha J. Khan, 2010, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2994161/

- Reference: Is affluence a risk factor for bronchial asthma and type 1 diabetes?, Tedeschi A1, Airaghi L., 2006,https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17014630

- Reference: Sugar intake is associated with progression from islet autoimmunity to type 1 diabetes: the Diabetes Autoimmunity Study in the Young, Molly M. Lamb, Brittni Frederiksen, Jennifer A. Seifert, Miranda Kroehl, Marian Rewers, and Jill M. Norris, 2015, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4529377/

- Reference: Biomarkers of β-Cell Stress and Death in Type 1 Diabetes, Raghavendra G. Mirmira, Emily K. Sims, Farooq Syed, and Carmella Evans-Molina, 2016, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5081288/

There is new research from 2022 showing gut dysbiosis in new onset T1D – I had always given probiotics to our girl with Down syndrome, and in later years made kefir weekly….but had stopped both a few months before her diagnosis. I can’t help but wonder…did I cause it? Other potential contributors: 1) she did get covid and 2) drank from a Berkey filter since 2018 which may have contributed aluminum oxide – supposed to be harmless) – we got rid of that part of the filter after learning about the Al-OH

Vitamin D deficiency in Arabia?

Maybe the clothing?

Yes, maybe! Here is a map of the prevalence of type 1 diabetes by country: http://tinyurl.com/yau9v4h6. Here is a map that shows where hijab (veiling of women) is practiced: http://tinyurl.com/ybq23tt7 It seems to me that this would introduce differences in the rates of vitamin D deficiency between men and women in the countries shown in green (mandatory hijab) on the 2nd map. If that were the case, research would need to be done to determine if there is a different ratio of type 1 diabetes between men and women in these countries. I couldn’t readily find an answer to that question online.

OMG Brian! That just scared me to death! I’m so glad you came home in time and were diagnosed properly!

Thank you for this blog post it was very helpful to me.